Have you wondered if there's a difference between dementia and Alzheimer's disease? I did, too. Like many people, I've used the words “dementia” or “Alzheimer’s” interchangeably (and used Alzheimer's far more often). Alzheimer's was my catch-all term for describing that whatever was wrong with that older person whose forgetfulness left me feeling really uncomfortable with them. They must, I would think, have Alzheimer's. When I was a little girl, we'd sometime say such a person was "senile," an old-school word which pretty much conveyed the same thing. Until a few years ago, though, I didn't use any of those words very often. And, until a few years ago, I assumed they all meant the same thing.

The Relationship between Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia

Well, they do. And, then again . . . they don't.

There is a relationship between them, yes, but dementia is not the same thing as Alzheimer’s disease. And Alzheimer’s is only one of many kinds of dementia. Oh - and senile? It's kind of an old-fashioned word describing the forgetfulness that comes with old age. We'll unpack this (and more) in the article, so keep reading.

When I was growing up, we’d sometimes say a forgetful older person was “senile.” Senile is kind of a nice word, I think. Even now, when I roll the word senile around on my tongue it feels rather benign. It brings to mind an picture of someone's sweet-but-foggy Auntie Marge, sitting in her rocking chair surrounded by loving, attentive family members and telling the same stories over and over again.

Nobody was particularly worried or anxious about Auntie Marge; the family just took care of her and that was that. Senility was considered a normal part of aging. By "normal," I mean that it was accepted that some elders became senile, and that’s just how life was). Because of the nuclear family (and village) surrounding her with its built-in flexibility and safety-net, Auntie Marge's cognitive decline would be inconvenient at times, but would probably not create a care-crisis in her family.

Back then, there existed both a family community as well as a “village,” or the larger community outside the four walls of Auntie Marge's home. If Auntie Marge wandered off, most everyone knew her and someone would take care of her until they could get her home again.

Many of us don't have that kind of safety net in our families any more; we're spread far apart, across cities, states, and even countries. Maybe there's been divorce or other relationship damage within our family that creates distance and separation even when we're only a few miles away. When a diagnosis sets the stage for long-term care, we don't have a "village," and that is not very helpful to our senile Auntie Marge or Grandpa George.

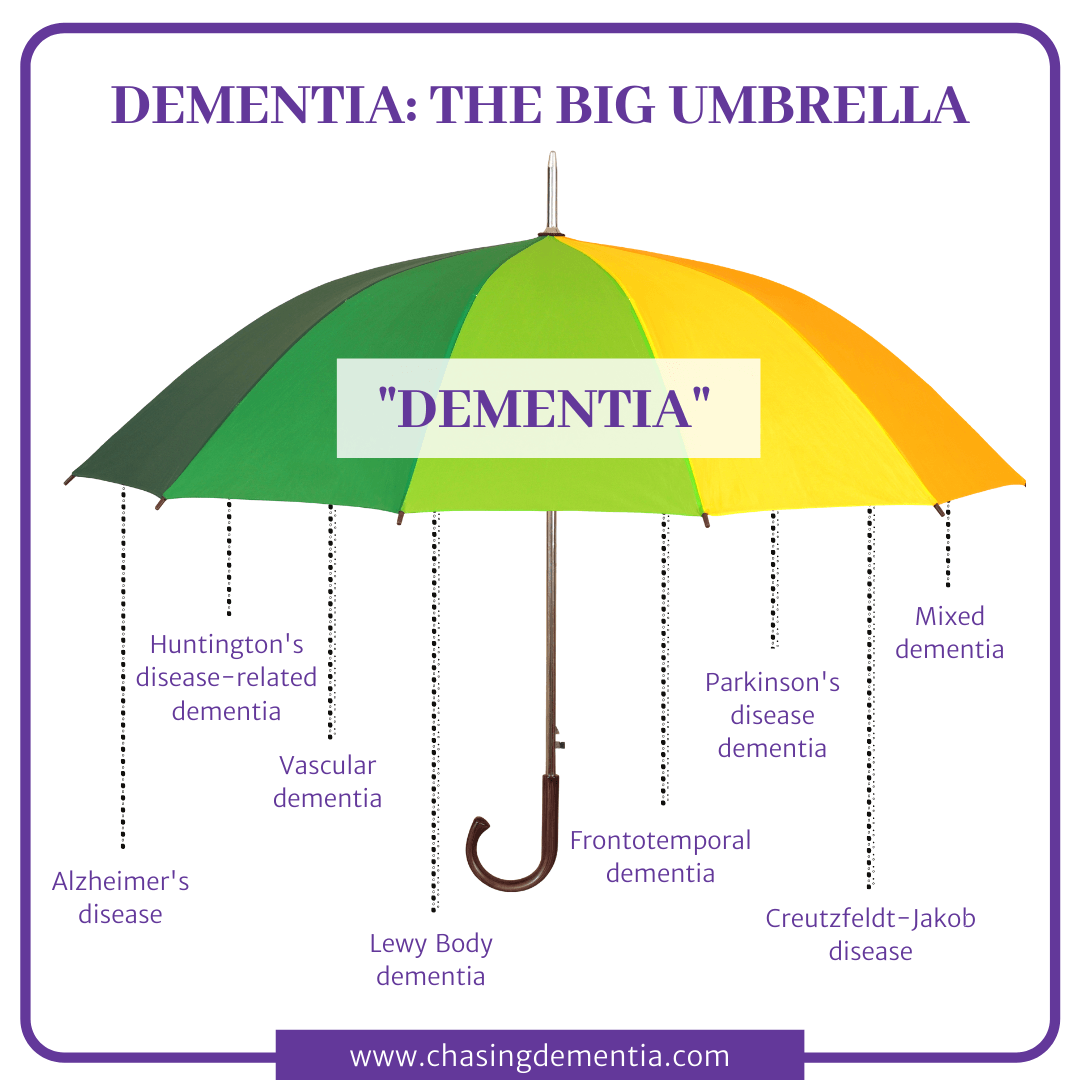

Alzheimer's is probably the most well-known name associated with dementia. However, while it might be the one most people think of first, it isn't the only type. We think of it first because it affects between 60 and 80 percent of dementia patients, making it by far the most common form of dementia. Alzheimer’s is a disease.

By way of contrast, dementia is not a disease; it is a descriptive term. It describes a group of diseases that share similar and overlapping symptoms.

Is it beginning to make sense? "Dementia" describes the mental and cognitive decline and changes that accompany a whole host of memory-related conditions, including Alzheimer's disease. If you collected ten individuals with dementia into one room, six to eight of them might have the Alzheimer's form of dementia, while a couple of others might have Lewy Body dementia. Another one of them could be living with vascular dementia, or even one of the others types. In fact, some of them might have more than one type co-occurring; they might have Alzheimer's and Lewy Body (like my mom did). They all have dementia; they do not all have Alzheimer's disease.

The Big Umbrella of Dementia

With that in mind, let me introduce the big umbrella. I didn’t invent the metaphor, but I love this way of illustrating the overarching dementia picture. Different conditions and diseases (like Alzheimer’s disease) fall under the big umbrella of dementia. I can’t even tell you exactly how many. Several years ago, during my earlier research on this, “more than 70" was a very common description. That figure is still out there, but this time around, researching in 2020, I’ve also read, “more than 100 types” and even “more than 400 types.”

I've come to believe that our ability to interact with our loved one successfully is greatly influenced by how much we know (or don't know) about dementia in general. The specifics of "which" type of dementia matter, don't get me wrong. But there are so many overlapping parts between the types that general knowledge is going to be very useful. Well, thanks to the worldwide web, any and every conceivable sort of information is just a click away. That means that in our modern world we can become familiar with something long before it impacts us personally. So, for example, someone might know about Alzheimer’s in a “Google” sense but not have interacted with a person who has the disease. We learn enough to use the word in casual conversation, sometimes in humor, but our understanding is (understandably) superficial.

A Deeper Understanding of Dementia

So, let’s go a step or two beyond that superficial understanding. Considering the “big umbrella” of dementia, a deeper understanding might look like this: someone can have symptoms of dementia, but not necessarily have Alzheimer’s disease.

They may be experiencing a noticeable decline in their memory, for example, which is a classic symptom of dementia, and a classic symptom of Alzheimer’s, as well . . . but without having other specific symptoms besides, they would be superficially perceived as having Alzheimer’s (using the criteria I mentioned a minute ago), or more accurately be described as having a mild cognitive impairment. Based only on the mild cognitive impairment, we would correctly say they have dementia, but without other, more specific symptoms, it would be incorrect to say they had any specific form of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s, Lewy Body, or one of the others.

Is It Normal Absent-Mindedness, Or Something Serious?

Is it possible to tell the difference between normal absent-mindedness and something more serious? If you know what to look for, yes. Let's take just a minute to talk about the average, run-of-the-mill forgetfulness that comes with "old age." That isn't dementia. It isn't even necessarily abnormal.

Our brains undergo changes as we age in the same way that our bodies do (for example, our bodies move slower, have some added aches and pains and less flexibility, etc.). Some people's brains change more than others, but are still within the normal aging range, while others will move out of that range into dementia. And some people really don't experience cognitive decline much at all as they age (lucky dogs!).

The in-between state where someone is definitely affected by a more significant decline than the low end of the normal range, but is not severe enough to be diagnosed as dementia, is called Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). MCI is a mental state that falls somewhere between normal aging and diagnosable dementia. It is not, however, dementia. It doesn't fall under the Big Umbrella.

So, if the memory or functional problems are worse than might be expected of an aging adult, but do not rise to the level of impairment seen in Alzheimer’s (or another kind of dementia), then it might be MCI.

I’ll talk about MCI in another article, but for now, let me reassure you that MCI is not necessarily a precursor of Alzheimer’s. Yes, it could be, but that’s not an absolutely fer-sure thing. Someone can have MCI and simply continue to have MCI without it progressing to something else.

Temporary Dementia

So far, we’ve talked about dementia that originating organically in the brain; dementia caused by disease. Dementia can also be caused by injury or other means. For example, head injuries, medications, hormonal changes, and thyroid imbalances have all been mentioned in the research as causes of dementia. [cite this] Some researchers even say that substance abuse can lead memory loss and dementia symptoms. [cite this] These are more situational in nature and are often reversible with proper medical care. Sadly, most of the kinds of dementia we’ll explore in this website are not reversible. They are the diseases of dementia – Alzheimer’s, Vascular, DLB, and others. But to speak to the “temporary versus permanent” question, I’ll say this: the diseases of dementia are progressive, irreversible, and ultimately, terminal. If the individual with dementia does not die from something else, like cancer or pneumonia . . . they will die from dementia. That is the sad truth, and the inevitable conclusion of the dementia journey.

The Dementia Journey Is Not Hopeless!

Dementia brings us to a place of harsh reality. Nobody wants to hear this, but I'm not going to duck the truth. At this time in history (2020), with no treatment or cure available, the prognosis of a dementia diagnosis is essentially “hopeless.” I suppose most people feel that way about a terminal disease. I'm approaching this conversation from a position of believing that it's really important to acknowledge the reality -- our loved one will die. In that sense, it is hopeless: we have no hope that they will survive dementia (based upon the medical reality at the time I'm writing this). But the journey is not hopeless, that is, your efforts are not hopeless, and that’s why we’re here. That's why I'm writing this. I want you to hear me: the journey through this Valley of the Shadow of dementia is not hopeless. Yes, it is brutally hard, it feels endless, and as caregivers and participants in the journey we are often overwhelmed. That said, we'll find hope and purpose in helping our loved ones finish well. Our job is to find and share (to the degree that it's possible) our hope and purpose – like bits of sunlight – in a very dark journey. Your loved one will perceive that sunlight in their own way. Even if you can't tell, their little antennae will pick up on the bits of hope and sunlight in you. It matters. Okay. Well, that was a bit of a rabbit trail, but I think it was important to add that. It is hard, but you can do it. You can. I want to help you – that's why I created this blog.

What Matters Most In The Dementia Journey?

The tagline of this website is “remembering what matters most.” Considering the subject matter, there’s a bit of irony in using the word, “remembering,” but it’s a word of enormous significance in the caregiver’s role. You see, your loved one may not remember things, but they still perceive things. They will have a perception, a sense, a feeling, of what is happening long after you think they aren’t capable, or you think they aren’t paying attention. Believe me – their antennae are still out and receiving input. They just interpret the input very differently than in the past. Even, sometimes, differently than in the past 10 minutes!

This will play out for you, the caregiver (or friend, or family member) in the task of weaving together moments that feed positive perceptions for them and accommodate the inaccuracies and misunderstandings they come up with. One of your most important tasks is to take what you remember, and change it up as needed to make it work for them. There is a famous quote that says, “They may forget what you said – but they will never forget the way you made them feel.”

This is true of your loved one. They will forget, they will fear, they will become frustrated and very, very, angry at times. What matters most is that they feel safe and loved, to the degree that they can perceive it. EVERYTHING needs to be planned and done with that in mind, even as you must accept that you can only do so much.

You Can't Make Their Brain Work Differently

I’ll say it again, because it’s so important that to get this: You must accept that you can only do so much. You simply can’t make their brain work differently than it will work. Because of the disease, their brain will create fear even if they are safe. Because of the disease, they will forget that you are faithful. Because of the disease, they may not trust you (they may not even recognize you). And because of the disease, they will become frustrated and angry at the ever-encroaching loss of their independence and control. In spite of all your best efforts, they will blame you! And you will struggle to deal with all of that. As we all do, at some time.

Still, you can love them. You can reassure them that they are safe, even if they won’t believe you. You can distract them. You can dig deep and find patience one more time. And – honestly – sometimes, you can’t. You’ll have to step away for a minute and collect yourself. It’s okay. It’s normal. It’s what we do in dementia caregiving.A Word To The Caregiver Who Was Abused By Their Loved One

What About Connection And Community For Dementia Caregivers?

First, know this: if your loved one lives in a memory-care facility and you "only" visit, you are still a caregiver. You do provide care – even if it is not related to overseeing their personal hygiene and medications. Don’t waste time feeling guilty; focus your time together on making the most of what you have. If your loved one lives with you, you already know how challenging it can be. You will rarely have a moment to yourself and might be too exhausted and emotional to make the best of anything! That’s okay; seize the few moments that you can and rejoice in those.

If you are doing the hard work of caring for your loved one at home, let me strongly suggest that you keep in mind the airline rule of putting your own oxygen mask on before you help the person you're traveling with, with theirs. You will not be able to go the distance if you burn out, get injured, or become ill as a result of your caregiving.

So, whatever your caring role, be kind to yourself. You'll forget things, not know things, overlook things, and lose your temper. Try not to feel guilty (but accept that it's a pretty typical part of the package and forgive yourself for your shortcomings). Ask questions, create your village, steel yourself to ask for and accept any help, and learn some of the ways you might improve your loved one’s life right now. Give yourself the same grace that you would offer a friend in the same situation. This is hard, but you can do it one moment at a time.

One way to “do it” is with community. It’s not quite the same as being in the room with you, but I welcome the opportunity to come alongside as a virtual resource and supporting shoulder. If you're interested in staying connected, and you haven't already done so, sign up for my occasional emails [HERE] and I'll keep you posted. (If you sign up twice, don't fret; the system will magically catch a duplication.) There's also a comments section (below) where you can say something about this article, and maybe others will join in to create a larger conversation. Finally, I have a separate contact form [HERE] where you can send questions or communicate privately via email, so don’t be shy about doing that! However you decide to do it, I'd love to hear from you! As far as I'm concerned, we’re in this together. Be blessed and carry on.